Songs of Blood and Sword, by Fatima Bhutto, throws more light on the fibre of Pakistani politics. It altered my impressions and complemented my reading of The Last Mughal Emperor, by William Dalrymple, and Cross Swords by Shuja Nawaz.

Politics of power is almost universal in practice, but, with dead bodies and bullets, it is interesting if not a sad story. Pakistan, that entire region, has seen violence from times immemorial. An ineffective judiciary and brutal police tactics are evidenced in the story of three generations of Bhuttos. They became the enemies of the state.

My impressions of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto (ZAB) were from after the 1971 war, when he, Nusrat and Benazir came to India for the Shimla Agreement. One couldn’t avoid knowing of them with the attention the Indian media was pouring on Nusrat and Benazir, yes just like Ms Khar got in the recent Indo-Pak talks. In the late ’70s (and even early ’80’s after ZAB was hanged), many shops in the Srinagar Valley brazenly displayed ZAB’s framed photographs and there were several Bhutto Committees. When ZAB was to be hanged, I clearly remember India was one of the countries that pleaded for his life. This does not find specific mention in the Nawaz and Bhutto books. India figures only in the conflicts, reflective of a psyche when it comes to India.

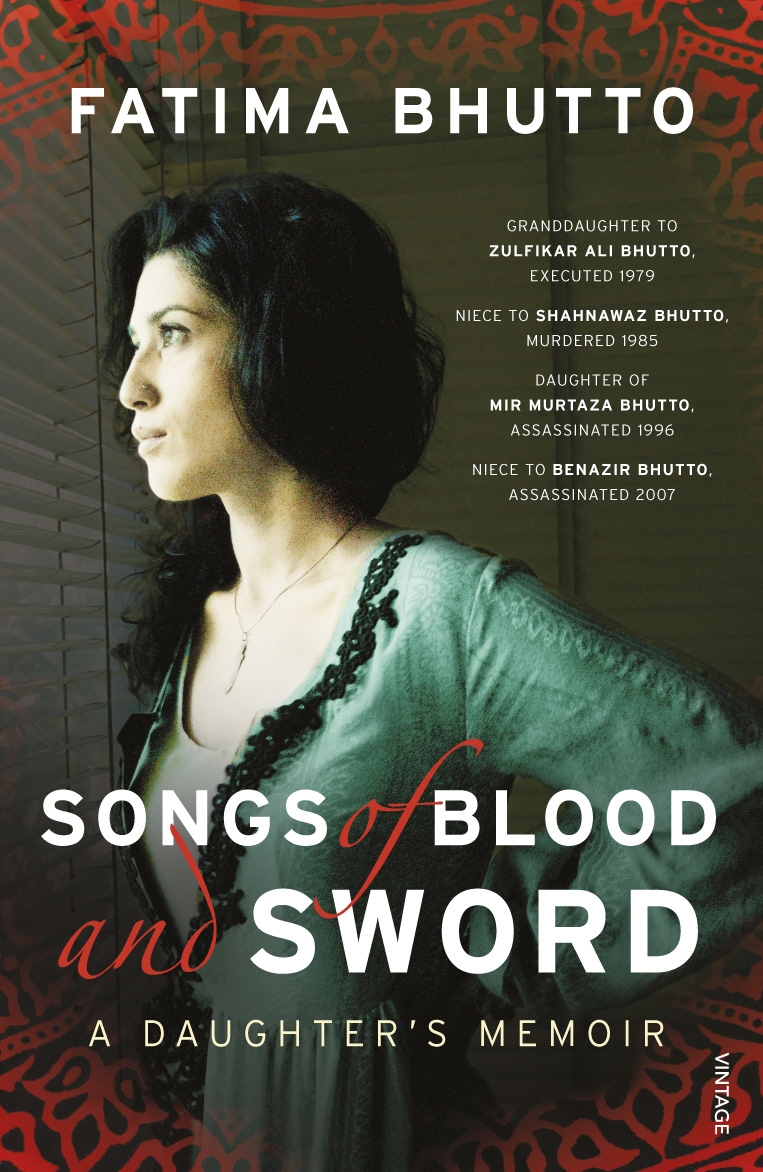

Songs of Blood and Sword, by Fatima Bhutto, the granddaughter of ZAB is well a written account of the elimination of her grandfather, father, uncle and finally aunt. The genesis for this misfortune is the rise and fall of ZAB. A complete picture can form only by reading both these books. Nawaz’s book has more detail on matters outside of the Bhutto’s saga. While it may seem unfair to put both the books into a class, they somehow help complete the contradictory macabre picture.

My impression of ZAB has changed after reading this book. ZAB was a very suave and intelligent person, who probably got a good deal in the Shimla agreement and he was a threat to India, especially since he declared 1000 (or was it 100) year jihad, in his speech at the UN. Nawaz’s book mentions the US and Pakistani ‘too-big-for-his-boots’ perception of Bhutto and Fatima Bhutto confirms the gruesome outcomes of it. Their deaths are a fact as much as their lingering charisma. Correlating this to Bhutto’s popularity in the Srinagar valley only confirms the charisma of ZAB and the popularity of his socialist policies in the non-feudal segment of the country. Had he taken a rapprochement to India, peace could possibly have ensued. I get a feeling, that there was a missed opportunity there, however farfetched it may appear.

If one were to study the cause and nature of unrest in the region, then this book was written about a feudal family that did not tread the natural course, (alas due to ZAB and Murtaza’s socialistic leanings), completes a trilogy with The Last Mughal Emperor from a historical perspective, and The Crosswords from an army one.

People of Pakistan not forming part of either the army or the feudal lot have little choice. The book reveals how ZAB’s son Mir Murtaza Bhutto, evolved to become a ‘threat’ and be declared as a ‘terrorist’. If this is the case with the affluent, I will not like to imagine the plight of the common people. Part of the reasons for gruesome dismissals from ZAB to Benazir Bhutto is the hot-headedness that comes from being feudal and martial. It was ZAB who asked his sons Murtaza and Shanawaz to avenge his death. Had he embraced reconciliation and atonement instead of retribution, the outcomes for the Bhuttos and Pakistan may have been different. Here again, I feel an opportunity lost, however naive the thought.

It was quite the fashion, if not the norm, to talk of Che Guevara, grassroots socialism and the ‘revolution’ in the ’60s. Very few took it seriously beyond a college fascination. The Naxal movement came out of the educated intelligent class, probably at the same time when the Bhuttos were articulating it. Murtaza’s ideals inspired by his father and the culture of the times are absolutely well placed. He even had outside support, which further substantiates ZAB’s international popularity. Yet as no one was able to come to his rescue and only sympathize, confirms that the establishment had had the leverage of its alliance partners. Nawaz’s book gives little credit to Bhutto when it comes to foreign policy.

It is a sad tale and evokes sympathy for the children and grandchildren; who were dragged into it for no fault. Ms Bhutto has only seen violence and perhaps judges the rest of the South Asian societies through her own experience. The region has many peace-loving communities and politics everywhere are definitely not as bloody as the Pakistani one.